miniJen and RISC-V

Short Introduction

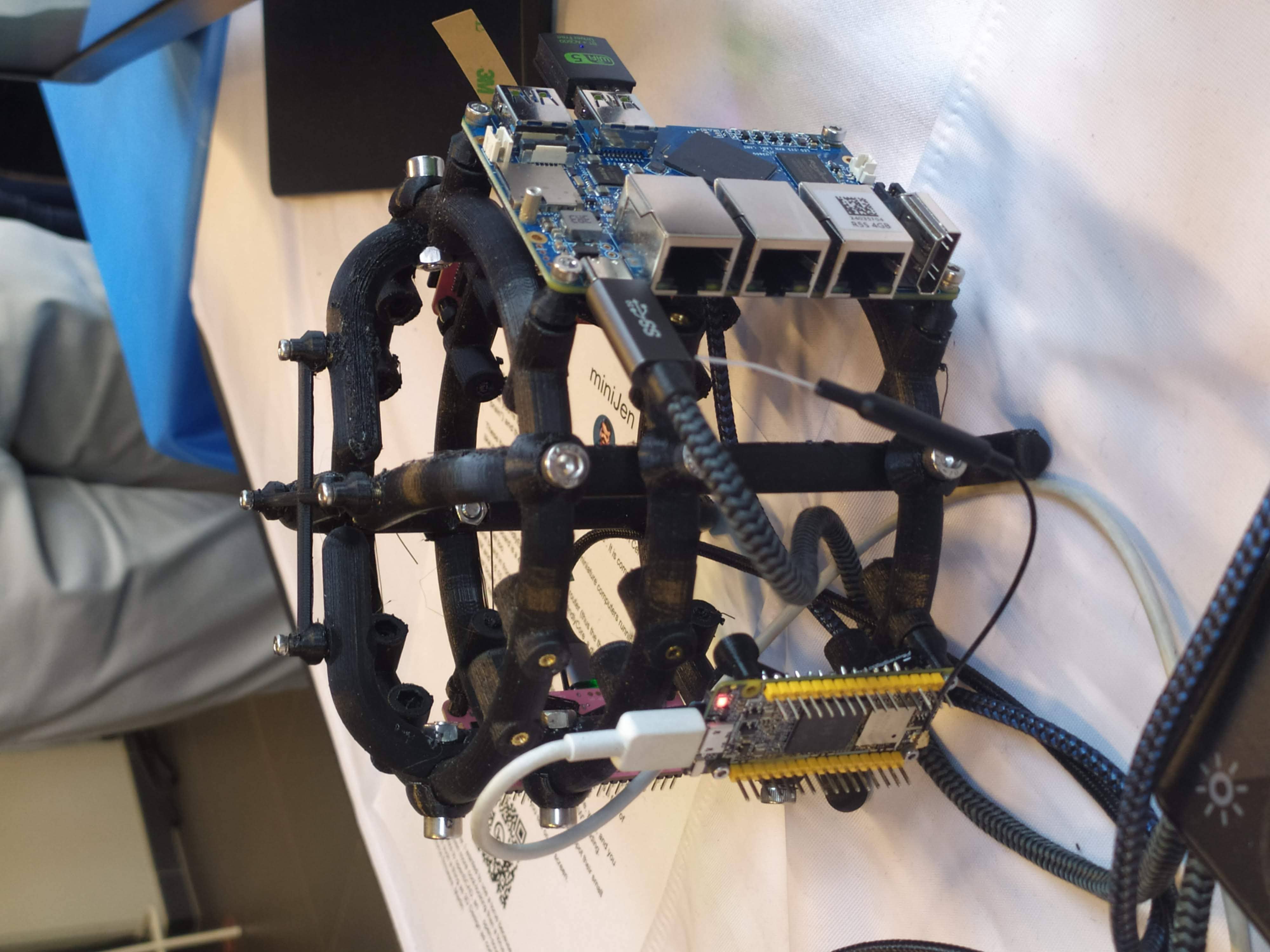

What is miniJen? It’s the Jenkins multi-cpu-architectures smallest instance known to this day.

It’s composed of a 4 arm Cortex-A55 cores RockChip controller (aarch64), a 4 arm Cortex-A7a cores AllWinner agent (armv7l), a 4 arm Cortex-A53 cores AllWinner agent (aarch64), and a single RV64GCV core AllWinner agent (RISC-V).

A bit of personal history

I’ve been an arm fanboy for years, it all started in 2014 or so when I bought a Raspberry Pi.

At that time, it remembered me of my younger days when I used to tinker with an HP-48SX calculator, using assembly language, discovering new methods, new instructions, and new backdoors every other day.

Later on, when resin.io (now balena.io) ported Docker to the arm processor, I then became obsessed with arm and docker.

I spent way too much time compiling FOSS for arm32 and aarch64, and building docker images around them.

It was fun, it was exploratory, it was a way to learn new things… and it was a way to contribute to the FOSS community.

I made a lot of friends, and I gained a lot of knowledge.

I sometimes had to recompile gcc with … gcc to be able to recompile ffmpeg for example, and one thing led to another, I had to recompile a library, then another, then a utility, then another library, then the kernel, then another library…

Boy, that was fun!

These were good times. I may sound nostalgic, and I think I am.

It was hard, but you got immediate or delayed benefits because then everybody was benefiting from the community work.

Be it for energy saving, IoT, Edge Computing, server rooms, Cloud, or just for fun, arm was bound to be everywhere.

It was the future.

Colleagues (who happen to be also friends, go figure) used to call me “mister WhatIf”. Yes, I had way too many ideas, but if you want to find one of these days a good idea, you have to let tons of ideas, good or bad, make their way into the world.

So yes, basically, I was spending most of my free time asking myself (and friends) “What if…?”.

These “What if…?” lead most of the time to an implementation on an arm SBC, because they were cheap and available at that time.

Some of these experiments were successful, and some were not (frankly, hosting a complete Gitlab server on a Raspberry Pi 3B was stupid), but I learned a lot from them.

Back to arm: when the future becomes the present, it’s not that exciting anymore.

Arm is not yet as boring as X86, but most of the software now works on arm, from microcontrollers to the Cloud, and the very last conquest to be made (laptops and even MacBook) has been won.

If you don’t own any arm hardware, nothing can stop you from developing for this architecture anymore thanks to QEMU and Docker.

It’s not that hard to compile the software for arm anymore.

It’s not that exciting anymore.

It’s not that fun anymore.

It’s not that exploratory anymore.

It’s not that rewarding anymore.

It’s not that challenging anymore.

It’s not that cool anymore.

It’s not that sexy anymore.

It’s not that… well, you get the point.

I still love the arm ecosystem and all the people I’ve met, but it feels like the honeymoon time is gone, we’re in a more platonic relationship now. It is stable, deep, and true, (I love the arm community!) but the time has come to find another quest.

The RISC-V quest

I’ve been lurking on the RISC-V community, projects, SoCs, SBCs, and vendors for a while now, and I’ve been following the RISC-V Foundation for quite some time.

But until recently, I didn’t have any RISC-V hardware to play with, and I was not seeing myself buying a very expensive but lame RISC-V SBC without any project in mind.

I was waiting for the right moment and the right project.

I’ve been working with Jenkins since April 2022, and of course, my love of arm being what it is, my first contributions were about arm32 and aarch64 for the Jenkins project.

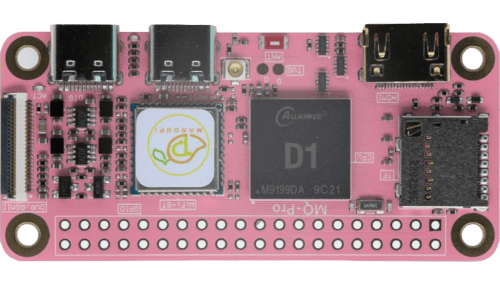

I spotted during the 2022 summer an interesting RISC-V board called the MQ-PRO from an unknown (to me) manufacturer called MangoPi.

The price was right, and the specs were not that good, but the board was available.

At that time, the software support was not that good, but I was not afraid of that (because of my personal history with arm). I did not buy it though, because I was not sure if I would have the time to work on it.

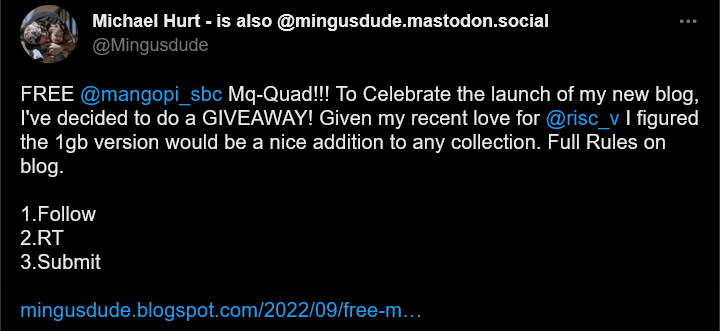

At the beginning of September 2022, the amazing Michael Hurt organized a giveaway on his Twitter account.

I won the board thanks to my proposal linked to Jenkins.

At that time, I had no clear idea if Java would run on RISC-V (and of course no clue if Jenkins would run on top of that), and I also knew Docker was not yet officially available for RISC-V.

That sounded way too fun not to try… especially since the board was basically free.

I then felt the same level of excitement I used to feel when I was working on arm32 and aarch64.

Yes, this was once again possible, new territories to explore, new challenges to face, new friends to make, and new knowledge to gain.

The RISC-V journey

Prerequisites and first steps

I had seen in the news that Ubuntu 22.04 was supplying a RISC-V image that could work for this board (designed for the AllWinner Nezha). The Nezha was the first D1-based board made available to the public. The MangoPi MQ-Pro came after that but shares more or less the same set of components.

As strange as it may seem (a RISC-V build by an Armbian contributor), I also found an image built by a regular contributor of Armbian, balbes150. I started by downloading Armbian_22.08.0-trunk_Nezha_jammy_current_6.1.0_xfce_desktop.img from December 06, 2002, burnt it thanks to Balena Etcher and was able to boot the board.

bret.dk gave me an interesting pointer to James A. Chambers blog post about the Ubuntu Preview for RISC-V.

In the blog post from James A. Chambers, there is a paragraph about OpenJDK Availability for RISC-V, and we can see that there is a wide range of OpenJDK versions (from 11 to 20) available here.

That was unexpected, I thought I would have to compile everything from scratch, make changes to the build system, and so on.

As you can see, the board is very minimalistic, we only have two USB-C ports (one being used for power), a microSD card slot, and a mini HDMI port.

My goal was to get this board on the Wi-Fi network, but how to do that without any Ethernet port?

Most of the time when I use Armbian, I just plug in an Ethernet cable, and I’m good to go, as the board uses DHCP by default.

I just have to search for a new machine appearing on the router webpage, and issue an ssh command to connect to it.

This time, I was kind of stuck.

I had no USB-C keyboard, no mini-HDMI cable, and no Ethernet plug to use.

What was I to do?

Once again, bret.dk came to the rescue.

Bret does tons of reviews on his blog and I found one about an Ethernet/USB hat for the Raspberry Pi Zero W.

I bought the same hat, a USB-C hub just in case, and a mini-HDMI cable.

The hat never worked for me for some reason, but the USB-C hub did.

It’s an almost-no-name generic hub, but it worked.

I managed to get Ethernet on it so that my board got an IP address from my router.

Linux and Java installation

Linux

I could then log in thanks to ssh, create an admin user, and so on.

I then removed packages linked to X11 that I don’t need for my use case.

Later on, I configured a Wi-Fi connection, and created a jenkins user.

The next step was logically to install the default OpenJDK 17 build provided by Ubuntu.

Java

I now know the default OpenJDK 17 build is a Zero VM build, so I also installed a nightly build of Temurin’s OpenJDK 20 and 19.

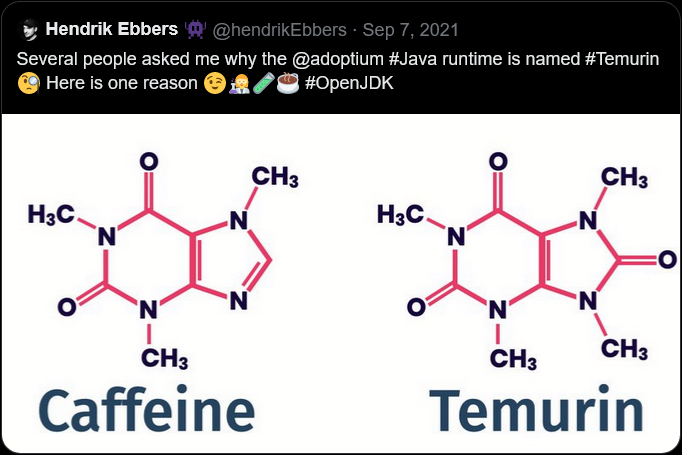

By the way, do you know what Temurin is?

Temurin is both a chemical similar to caffeine and an anagram of “runtime”. Oh, and a cool new free-to-use Java runtime from the Eclipse Foundation! Enjoy.

Zero VM

You may wonder what is a Zero VM build, and why I want to use something else.

Zero VM builds come with pros and cons.

- Zero VM is a Java Virtual Machine implementation that is designed to execute Java applications on systems that use architectures other than the x86 architecture. It is specifically optimized for systems that use ARM, PowerPC, and other non-x86 architectures.

- Zero VM is part of the OpenJDK project, which is an open-source implementation of the Java SE platform. Zero VM uses a technique called “interpreter-only” mode, which allows it to run on platforms that do not support just-in-time (JIT) compilation.

- In interpreter-only mode, Zero VM executes Java bytecode directly, without compiling it to native code (it does not use any assembler). This approach typically results in slower performance compared to JIT-enabled VMs, but it has the advantage of being able to run on a wider range of platforms. That’s why the developers got a working OpenJDK to build this early for RISC-V.

So, as much as I’m grateful for the Zero VM build, I’m also curious to see how Temurin’s builds perform on this board.

Said in another way, the board is already so slow that using a Zero VM will make it unusable.

There, I said it.

The default OpenJDK implementation is there just in case I need to use it for some reason, but I plan to only use Temurin’s builds.

OpenJDK 19

As you may already know, JDK19 is almost end of life (21st of March 2023), so I’m not going to use it for long, and Temurin does not provide steady RISC-V nightly builds.

Speaking of end-of-life, I could not recommend enough endoflife.date which is an open-source project that aims to provide a simple way to find the end-of-life dates of software and operating systems.

It even provides an API to query the data.

Thanks a lot to Mark Waite for letting me know about this project.

Back to openJDK19, how did I find the last RISC-V published nightly build?

While discussing with Stewart Addison on various GitHub issues related to Temurin onRISC-V (and aarch64) and later on through Temurin’s Slack channel, we sympathized.

He mentioned that he had the same board as me, and gave me a link to the latestRISC-V build he could find.

So, that’s the version I’m using for now.

Please note that your libc should be at least 2.35 for this build to work.

The RISC-V Jenkins agent

Installation

I then added an ssh key on the RISC-V machine that would become an agent, created a new node within the Jenkins UI, and installed the agent on it.

Testing

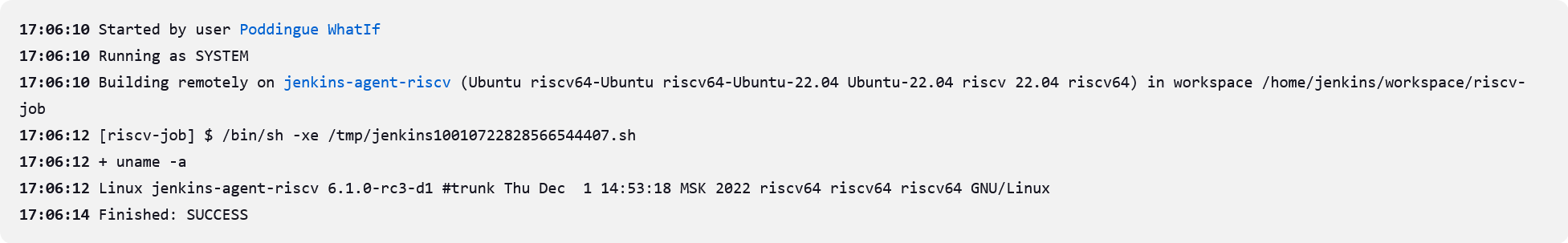

The last thing to do before asserting Jenkins works on RISC-V was to launch a simple RISC-V job.

Spoiler alert, it did work!

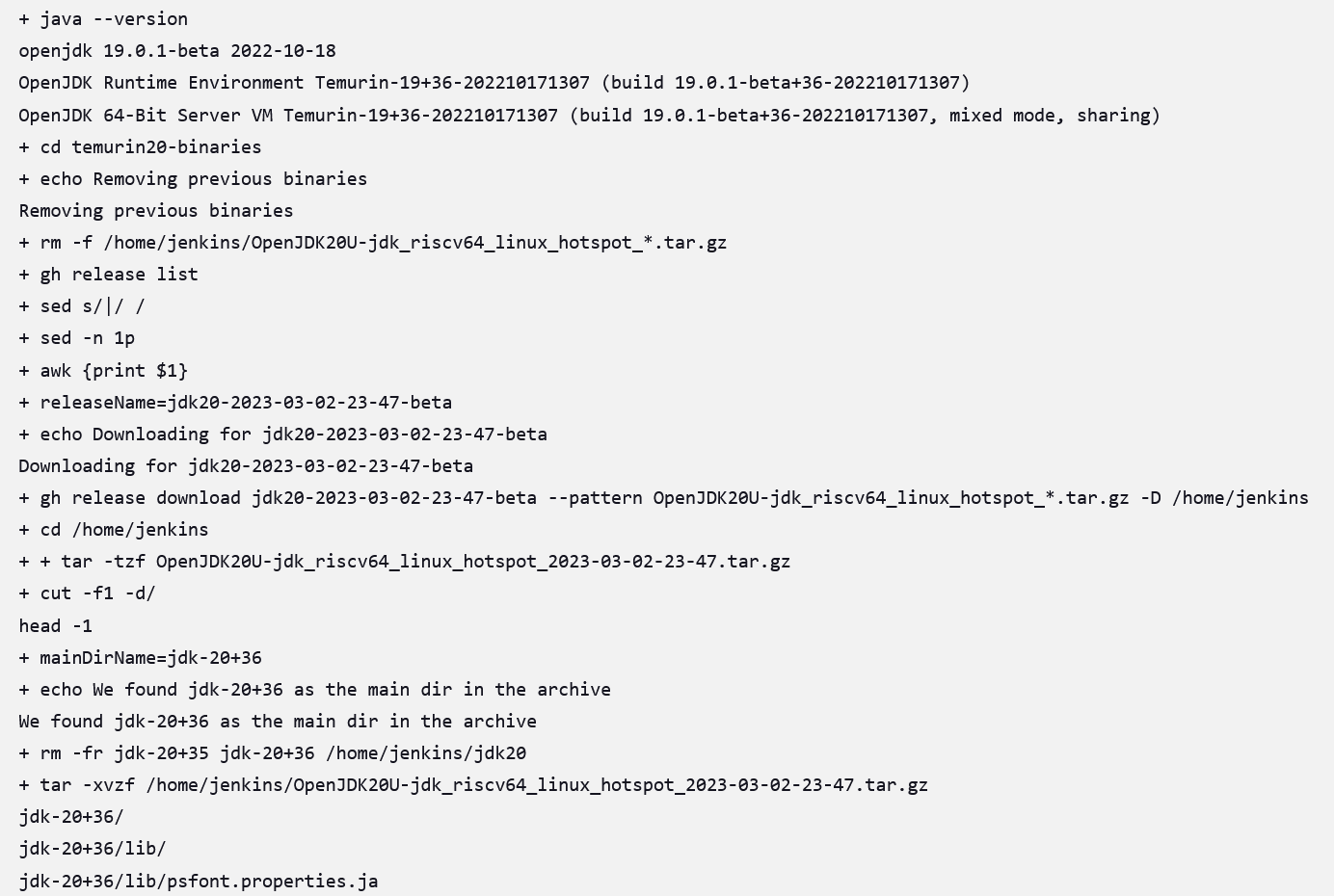

The next stop was to install a Pipeline that downloads the latest nightly build of Temurin openJDK20 and installs it on the RISC-V machine, overriding the one I installed earlier.

This is done mostly thanks to the gh command line tool that can do wonders when it comes to interacting with GitHub on the command line.

gh is open-source, and it’s available even for RISC-V, but not directly in the gh GitHub releases.

As far as I know, go is not yet officially available for RISC-V, and gh is written in go.

So… What’s the catch?

Well, it’s open-source, and Ubuntu has a source package for it.

Even if I can’t see the binary package for RISC-V on the Ubuntu package page, it magically appeared on my machine after an apt install gh.

The Pipeline uses openJDK19 to update openJDK20, and openJDK20 to update openJDK19. The main Jenkins process is still running on the Zero VM openJDK17. That’s something I’ll have to address later on.

That part worked, and I was pretty happy about the result.

But what about a smoke test?

I mean, I’m not going to use Jenkins on RISC-V if I can’t build a real-life project with it, right?

I asked in the community, and Mark Waite, Basil Crow, and Damien Duportal all agreed that the best way to test Jenkins on RISC-V was to build a few Jenkins plugins with it.

I started with an ambitious project, the git plugin itself.

Well, it was quite big and not ready for openJDK19, so I switched to a smaller one, the git client plugin.

Same player, play again. It did not go well either.

I then switched to a very basic one, the infrastructure test plugin, which is used to test the Jenkins infrastructure as its name implies.

Bad luck once again, as it was not ready for open JDK19 either.

In desperation, I switched to the Platform Labeler which is ready for openJDK17, but… it required way too much memory to be built.

Bummer!

There, I was stuck.

To this day, I haven’t found a Jenkins plugin that can be built with openJDK19 on RISC-V with very little memory.

I have yet to find another kind of smoke test that would prove Jenkins works on RISC-V… or wait until a plugin is ready for openJDK19.

The RISC-V future for Jenkins

Back to the future

When it comes to Jenkins and the RISC-V ecosystem, I swear I thought I was some kind of pioneer, like in the good old days of arm.

Guess what, I’m not!

I’ve finally done my homework and found out that Jenkins has been running on RISC-V for a while now.

- In a blog post from May 2021 (which has unfortunately disappeared), the

RISC-VFoundation demonstrated Jenkins running on aRISC-Vboard with a Linux operating system. The demo used the OpenSBI bootloader and the OpenJDKRISC-VPort to run Jenkins and was able to successfully build and test a simple Java application. The post includes detailed instructions for setting up Jenkins onRISC-Vand running a build job. - In a video of the presentation (which has unfortunately disappeared) given at the LFELC Spring 2021 Virtual Summit, we could see a demonstration of Jenkins running on

RISC-V. The presentation was given by Anup Patel, who was at that time a member of theRISC-VTechnical Steering Committee. - There is another video (which has unfortunately disappeared) that shows Jenkins running on

RISC-V, presented by Keith Packard at theRISC-VWorkshop Taiwan 2021. The video shows Jenkins running on a HiFive Unmatched development board, which is based on the SiFive Freedom U740RISC-Vprocessor. - In a Reddit thread from January 2021 (which has unfortunately disappeared), a user reported running Jenkins on a HiFive Unmatched

RISC-Vboard using Ubuntu 20.04 and OpenJDK 11. The user reported that Jenkins worked well on theRISC-Vboard and was able to run build jobs without any issues.

Why have these experiment proofs been removed? Is that a coincidence or am I acting undercover to remove any evidence of Jenkins running on RISC-V before I attempt to do the same?

Just kidding, I have no idea, but if three years ago some people were able to run Jenkins on RISC-V, I should be able to do the same today.

The RISC-V board I’ve been using for this experiment is not the most powerful available on the market, so my success rate with Jenkins plugins was not very high.

I have another board that is way more powerful, so I’ll try again with it soon. It’s the StarFive VisionFive 2 board which is based on a quad-core RISC-V processor (the StarFive JH7110 64 bit SoC with RV64GC).

It also sports 8GB of LPDDR4 so I should be able to build a few RAM-hungry Jenkins plugins with it, and why not, even run a Jenkins controller on it.

I have another board on my radar; it’s the Vision Five 2’s twin from Pine64, the Star64. At the time of writing, it’s not available yet, but I’ll definitely get one as soon as it’s available.

When will RISC-V be a first-class citizen with Jenkins?

Remember, Jenkins is an open-source project, but above all, it’s a community project.

Who am I to tell you when RISC-V will be a first-class citizen with Jenkins?

I’m just a guy who’s trying to make it work.

I think it’s up to the community to decide when RISC-V will be officially supported by Jenkins. My guess would be when two major conditions are met:

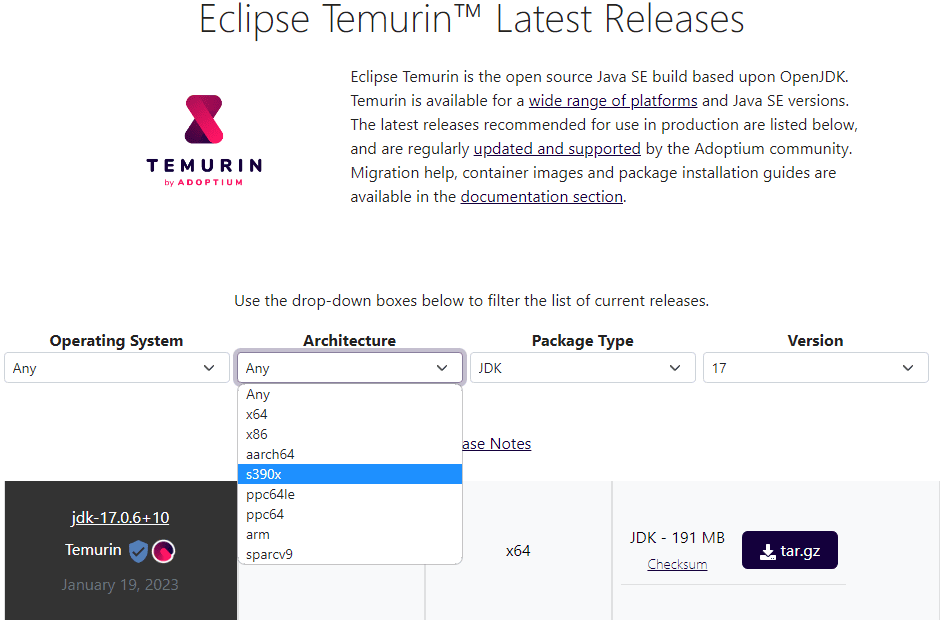

- Temurin is officially available for

RISC-V, which means we’ll be able to download a binary package forRISC-Vfrom the official AdoptOpenJDK website.

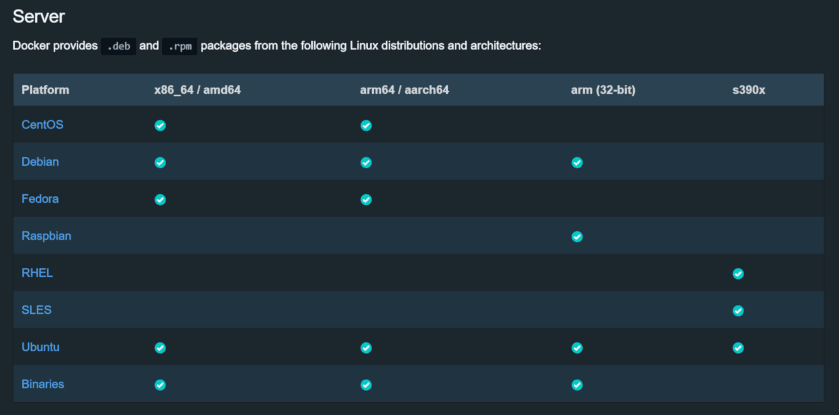

- Docker is officially available for

RISC-V, which means we’ll be able to download a binary package forRISC-Vfrom the official Docker website.

You may wonder, why I need Temurin and Docker to be officially available for RISC-V before saying Jenkins supports RISC-V?

As you know, the Java motto says:

“Write once, run anywhere”

It’s often abbreviated as “WORA”. This motto reflects Java’s ability to be compiled into bytecode that can run on any platform with a Java Virtual Machine (JVM), without requiring recompilation for each specific platform. The Jenkins war runs on top of the JVM; it is then considered CPU-architecture agnostic, which means it can run on any CPU architecture (as long as openJDK11+ can run on the machine, but take it with a grain of salt).

The Jenkins infrastructure owns (or borrows) machines of the supported CPU architectures and runs the war on them, so we can testify Jenkins works on these architectures.

Jenkins also supplies Docker images for the supported CPU architectures and tests them on the supported CPU architectures.

The Jenkins project does not own any RISC-V machine, as far as I know.

We could provide a RISC-V docker image, as docker buildx allows us to build for various CPU architectures, but… Wouldn’t it be kind of hasty?

We wouldn’t be able to test on a Jenkins-owned, Jenkins-managed machine regularly.

It is then urgent to … wait.